(Previous Chapter: The Chinese Bar)

Street of Rogues Ch. 11—Chuckie’s Sweet Sixteenth

The best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men

Gang aft a-gley.—Robert Burns.

In my case, it was more a matter of running with the pack than it was any real desperation for drug money. Rumor had it that there was as much fun to be had burglarizing drug stores as there was profit in getting away with it. Case in point, the wild pill fight that took place during one of the burglaries. Wow, that sounds like fun! Plus, it would address the very heart of our daily reason for living, which was getting high.

While we panhandled and schemed for loose change, there were pots of pills in the local drugstores. It made sense to skip the middle-man and go right to the pharmaceutical source. Even a modest haul of unidentifiable pills could be bartered and exchanged for other drugs. And cash.

We were inspired by the challenge and its potential rewards, which could be a veritable windfall of pills and other assorted paraphernalia, such as syringes and needles—maybe even cigarettes. The stores were insured, so we thought of breaking and entering as a victimless crime. We’d rob from the rich and keep it because we were broke. It’d be our own version of ‘Robbing the Hood,’ and it put a twinkle in our eyes.

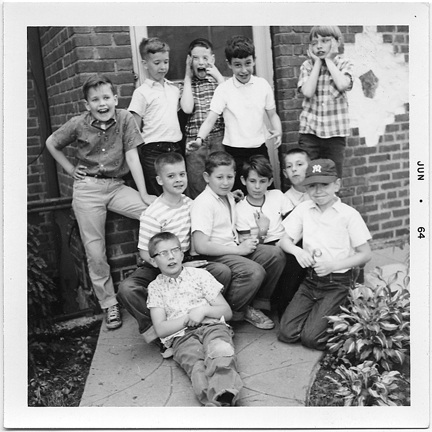

Chuckie, Lewis and I met up at the park the following night on Chuckie’s sixteenth birthday, stoked and primed to plunder. Chuckie wore all black. With his knitted hat, he reminded me of Michael Parks’s Then Came Bronson character from TV, the guy who aimlessly rode his bike across the country. I wore a navy blue, double-breasted suit jacket I had picked up at a second-hand store for seventy-five cents. In the forties it was a nice suit, and had lots of deep pockets. The old man who gave it up probably never expected Bozo would wear it on his way to a drugstore heist in 1970. Lewis wore what he always did, which was no more than a long-sleeve shirt, pants and sneakers. He slicked his hair back, ready to go. I cracked my knuckles and twisted at the hip, popping a few vertebrae. I was loose, alert, and amped-up to… Do what, exactly?

“How, exactly, do we break in?” I asked them both. Throw a brick through the window?

“Ready?” That was Lewis’s answer. They were ready, so I guessed I was, too. Lewis led the way.

For our first target we chose the biggest drugstore in the area—one that used to be a bank, in fact. I was skeptical but enthusiastic. We headed over and approached our targeted Bucket-o- Drugs from the dark side of the commuter railroad tracks, where Lewis mentioned the customary (though needless) warning about the third rail—the hot one that could toast your body into a smoking cinder and turn your hair blond. I had been putting coins on those tracks for years as a kid, running around trying to find them once a train had run over them. We had all heard hundreds of gory stories about the poor schmucks who were fried stepping on the hot rail. Chuckie told us about a drunk he heard of who pissed on one and got electrocuted through his dick. The tale was always followed by a long moment of silence.

What a way to go!

We climbed up a ventilator shaft to the roof, passing a window on the way up.

“Hey, I think this is the clothing store where my sister’s boyfriend works. They got some good shit in there,” I said.

“Some other night,” said Lewis, foretelling the future and beckoning us from above.

Once we were on the roof, we made our way across its shadows toward the drugstore half a block away at the corner. Lewis and Chuckie were lookouts while I went in for a closer inspection of what appeared to be a hatch. I had to climb to a lower section of the roof to check it out, and sure enough, it was a hatch door. It sat between two ventilators, semi- sheltering it in shadows from the lights on the street.

Lewis instructed me, “Pull it off.” I held my breath and lifted, slowly, ready to bolt with the first note of alarm. There was a momentary resistance as I tugged at it, a little snap, then it came free—dangling a thin, loose wire. I listened like a gazelle at the water hole, straining with every billimeter of both ear drums for any alarming sounds, perfectly still, not even breathing. There were no alarms that we could hear, so I took a peek inside and whoops! There were moving shadows down there! Quickly checking my watch, it was 11:00 pm on the nose.

I fumbled to replace the hatch cover. “Shit!” I stage-whispered, “Fuckin’ place is still open!”

“SHHHHH!” Lewis shushed from his lookout twenty or so paces away. I froze again, exposed on open terrain. Now I could hear bells coming from the street, faint from up there but sounding like they must be loud down below. No one had to say Run for it! Christ! as the three of us sprinted away like a covey of exposed quail.

How can we be so fuckin’ stupid as to break into an open store!? We dove off the roof at full tilt, slammed through the bushes, dashed over the railroad tracks like football players on tire drills, ran down the steps from the train station and around the corner, where we skidded on the brakes and strolled casually—idle boys out for a cakewalk, trying not to look sweaty and out of breath. We lit smokes, whistled affectedly and looked as innocent as possible as we approached the front of the store, the alarm still blaring.

Lewis hunched over and loped with his hands covering his ears. “The bells! The bells!” he said, as if Quasimodo impersonations might somehow clear us of all suspicion.

We could see two guys in the store presumably talking about it as we continued past and crossed the street to hang out in front of the pizza place, which wasn’t unusual, but not particularly inconspicuous. Meanwhile, one of the drug store guys disappeared into the back of the store. A minute later, the bells and sirens stopped. Then the lights went off, but we could still see him come back out front and chat with the other guy for a while. Apparently coming to a conclusion about what to do, they left the building. Locking it up, they just walked away.

“Figure they shut it off for the night?” we wondered among ourselves, strolling in a tight knot. There was only one way to find out…

We waited over an hour, cruising back and forth to check for cops or someone they may have sent to fix the alarm, but there was nothing; no one showed. Grabbing a slice of pizza before they closed, we reconnoitered the place some more with pizza juices dripping down our sleeves. We waited patiently, biding our time. We had all night if necessary, though I’d have to call my parents and let them know I was all right. Pretty soon we reckoned the place was wide open, beckoning to us like a native girl in front of a grass shack.

“It seems, gentlemen, and I use the term advisedly…” I pronounced, “…that the coast is as clear as it’s gonna get. Shall we do a little shopping?”

Chuckie rubbed his hands together. Lewis’s eyes were wide open and gleaming. This was the ultimate pot at the end of a gritty city rainbow. We had caught our leprechaun and were as prepared to let go as a pit bull might feel about a favorite body part.

I still couldn’t believe it could be this easy. How can we be so fuckin’ brilliant as to break into a store that’s already open!?

We went back, quietly and without banter this time, until we were in position —the three of us crowding the hatch as if it were a meeting on the pitcher’s mound.

Lewis offered some last-minute instructions. He hadn’t done this before either, but obviously researched it. “Watch out for tripwires and electric eyes. Oh, and cameras.” He looked at me, “You stay here and lookout, we’ll pass the shit up to you.”

“Right, got it.” Let them do all the work and I’ll just sit here nervously in the barely concealing shadows of the roof, from where I could see into the windows of the upstairs apartments across the street. I’ll just hunch here and try to look like a misplaced gargoyle.

Popping the hatch, its puny lock dangling along with the alarm wire, they made their way down the convenient ladder leading to pay dirt. “Stay low,” I whispered after them. Then they were the moving shadows below, friendlies at work.

The wait was interminable. They were down there a good eighteen minutes without a word. I needed a smoke badly but didn’t dare light up. Instead, I fidgeted with my lucky lighter, reading the slogan again. Life. To see life, to see the world, to eyewitness great events week after week.

Another five minutes passed before Lewis finally poked his head out of the hatch and took a sniff around before climbing out. Chuckie quickly followed, and neither was carrying anything. I didn’t have to ask; something went wrong. “Can’t find the good shit,” Lewis said, wiping his hands. He was put-out and irritated.

Chuckie wouldn’t give up the chase until it played out its destiny, good or bad. “There’s a metal cabinet that’s locked,” he said. “It must be where they keep the good shit.”

“How big is it?” I asked.

“Too fuckin’ big, that’s how big,” Lewis said, but he had an idea. “Van Heflin lives down the block. I know his old man has an acetylene torch. We’ll burn it open!”

“Torch it open?” I hazarded a wild guess, “That’ll take forever!” I could picture him with the face guard and leather apron going to work down there—a giant sparkler in the shadows.

“Got any better ideas?” I didn’t, after crossing off bashing it in with rocks such as cavemen might, or tipping it over and jumping up and down on it like chimpanzees.

Chuckie and I waited across the street while Lewis pebbled the correct window. Van Heflin lived in one of those upstairs apartments above the stores. His old man was a boozer and beat the crap out of him if he even suspected he was fucking up. Van Heflin, in turn, beat the shit out of anybody who might have given the old man that notion, so we retreated to the rear and let Lewis handle it. Van Heflin didn’t have weights to work out with, so he bench-pressed his living-room radiator fifty times whenever he walked through the front door. That sounded inconvenient, but it succeeded in giving him a body of steel. Eventually, the big, ruddy bulk of Van Heflin emerged from the front door, quietly carrying his shoes and a crowbar.

Lewis explained the deal to us. “I had to let him in on what we’re doing, but he doesn’t want a full split. He just wants something for the use of his crowbar. We’ll throw him a bottle of goofballs and he’ll be happy.” Van Heflin came up behind him, still adjusting his shoes.

Chuckie and I greeted him in unison. “Yo—”

“Let’s go, man. I gotta get back before my old man sees I’m gone.” We crept back again, professionals this time. Now it was personal. We couldn’t let this opportunity slip away into what-ifs. With the hatch away, and Van Heflin backing us up as lookout on the train platform well above the roof, down we went into the shadows. It didn’t take long this time. After Lewis notched the cabinet with the crowbar, Chuckie grabbed the door and ripped it open with his bare hands—proving an impatient adrenaline rush is more powerul than a iron rod. Inside, the thing was crammed full of the good shit. Big, bright bottles fairly sparkled under their own power in the dim streetlight and the shadows it cast inside. Seconals, Tuinals, Nembutals, Phenobarbitals—all the -als were represented, a great congress of them. There were legions of fresh pills—whole batallions of Dexedrines, Miltowns, and what we called Cartwheels and Black Beauties, shining behind color-coded labels.

“Resplendent Drugs,” I would have called the photograph, had I been able to take a picture. We giggled in awe, if that’s possible. It was beautiful. Before long all of them were being hastily swept into three large grocery bags that were open at the top and overflowing. I was stuffing the leftovers into every pocket I had until we literally had all we could carry up the ladder, a conga line of pills and other saleable pharmaceutical stuff.

I caught Lewis topping off his sack with a box of surgical gloves. “What the hell are you going to do with those?”

Chuckie snickered. “Sell ’em to a proctologist?” His mother was a nurse, so he knew what he was talking about. I had to gather the meaning from the context of his sick grin.

I laughed. “Maybe he uses them himself.” Lewis also had a box of cotton. I was pretty sure we didn’t need it. The cotton out of a cigarette butt was good enough to cook smack in.

Chuckie agreed. “He’s right. Lose the cotton, but keep the gimmicks!” There would be no argument from me about the syringes and needles; these were the finely-honed .22 pointers that went in so nicely. Having a ready supply of works sometimes bought you into a share with someone else’s stash. These were pharmaceutical grade, sterilized needles and, as such, much easier than having to put one together on your own with an eye-dropper and a baby pacifier. Besides that, anything you could offer a cranky junkie was just cause for carrying it around. It was always best to get on their good side from the onset. We looked around for smokes but they didn’t have any—which was just as well as we would have had to carry them in our mouths or smoke them all before we left.

“Let’s get the fuck outta here.” I split, teetering with my bag up the ladder. Climbing out, I looked for Van Heflin, gave him the thumbs up, and he disappeared into the bushes near the tracks to wait for us while we made our way across the roof. I stayed to grab the bags from above while Lewis and Chuckie came topside.

Lewis neatly put the hatch back in place, “So it’s not so obvious.”

“I think it’s pretty fuckin’ obvious already, man,” I told him.

Lewis looked almost offended. “From the outside.”

“Oh.” In case the cops decided to patrol up there, I guessed. I gestured grandly ahead with a wave of my hand, employing an old Groucho line, “Lead on, Kapellmeister, my regiment leaves at dawn! Ladies first.” Lewis smiled and got going.

We sloped along, trying to blend with the shadows. Ahead of me, Lewis picked up the pace once we got into more open territory. We were halfway across the roof to the jump-off spot and there were still no sirens or alarms going off, or red lights flashing on the street. I was beginning to feel like we’d make it, and what a fuckin’ haul! It was far more than I’d ever seen in one place, practically dump trucks full of the stuff! I tried a rapid calculation of how much money we held bouncing in our hands at twenty bucks per hundred pills, but failed. It was inconceivable, like trying to guess the number of jelly beans in three huge jars.

As we hit wide open territory, starting to giggle and laugh outright now, a sense of urgency overcame us and what started out as a slippery getaway soon turned into an unruly rout off the roof. The three of us tore across the rough tar-paper in peals of laughter. Bottles were trying to jump out of the bags and my pockets. I held tightly onto the top and bottom of my shopping sack, determined to not lose a single one, running like Groucho Marx. I looked over at Lewis just in time to see him kick his front foot with his back foot, tripping himself. I watched, horrified, as he hit the scratchy tar paper, where he stuck, with his feet falling over his head in some weird spider-like position. Hundreds of white pills scattered fan-like in front of him. Bottles rolled everywhere, but only the Carbotrals busted.

“Holy shit!” I said, stopping to help him get all the pills back in the bag, even the spray of Carbotrals that were lying so brightly against the black roof, and boom, just like that we were off and running again, trying to catch up to Chuckie waiting on an AC unit near the roof to help us get our booty down.

“You okay?” I asked while running, trying unsuccessfully not to laugh. I knew at least nothing was broken, which was good because I didn’t want to have to use him as a dogsled in order to carry him and all the goods to safety. Chuckie was belly laughing as he helped us down, trying not to tumble into the bushes. By the time we were back on the ground below the railroad tracks, we were in hysterics. To this day I can’t forget the sight of Lewis coming to such an abrupt halt on his chest. Even he was laughing, while checking for scrapes and skidmarks.

We made our way up the hill to the tracks, resting on a rail while waiting for Van Heflin to find us. With our hands on our knees, huffing for air, smiling and laughing between deep breaths, Van Heflin showed up and stood with his eyes and mouth wide open, staring at the haul.

Lewis handed him his crowbar, then fished out a giant bottle of three-grain Tuinals and held it up to him. There were three hundred pills in there, the best goofball money could buy and thieves could steal. “That okay with you guys?” he said, respecting his partners in crime by asking. Considering that it hardly made a dent in what was left in the bags, as well as all our pockets, Chuckie and I agreed magnanimously.

Van Heflin took the pills like they were a Xmas present. He smiled real big, turned and bolted for home. With a couple of those in his bloodstream, his old man could beat on him all day and he’d hardly notice.

First, we needed to organize ourselves. We stuffed bottles overflowing from the bags into more concealed places on our persons; bulking up by sticking them up our sleeves and down our pants, with some small ones in our socks. One friendly slap on the arm and I would be digging glass out of my armpits for a month. I felt extra vulnerable and slow to move. You never knew who you might run into in the streets at that time of night. Nobody good, most likely. There would be some embarrassing questions, some frisking, some running….

Looking either comical or deformed, depending on your outlook, we realized two loopholes in our non-plan. First, how do we get to where we’re going carrying three huge bags with pills without looking so guilty, and secondly, by the way, where are we going with all this shit? We had to sit down in the open somewhere just to see what was there and divvy it up so we all had the same variety. But where? Only my room in the basement was big enough to possibly get away with it, but I didn’t want to take the chance. Besides, I didn’t really have the facilities necessary to lay it all out in the care and luxury it deserved. I also didn’t want to get inconveniently busted by my parents and end up blowing the haul down the toilet as a result.

Lewis snapped his fingers and stood up. “I got it, let’s go.”

Chuckie and I looked at him without moving. “Where?” we asked.

“We’ll go to Jill’s apartment.” It took a few seconds for it to sink in which Jill he was talking about.

“Ha—”

I interrupted Chuckie, “Jill? You mean that big-assed junkie with the crazy, four-year-old kid? The one whose husband keeps sending her stereo stuff from the PX in Nam that she keeps hocking for cash? The guy she never knows when he might come home? The Jill that—”

“She’s harmless,” Lewis said. “Got any better ideas?”

“—lives two miles from here, across the boulevard?” Queens Boulevard wasn’t just any regular boulevard, it was eight lanes of concrete you couldn’t get across on one green light unless you were running. I’d seen many an old lady dehydrate out there on a hot day before making it across. It was a windy no-man’s land, with cars whizzing by just inches from your kneecaps.

“Look, we’ll take the side streets after we get across the boulevard,” he argued, which was the only way to get there anyhow. Chuckie and I knew how to get there. Lewis was just pushing his case, and there simply wasn’t an alternative.

“The sooner we get there the better,” I said.

Chuckie jiggled a couple Tuinals in his hand and grinned. “And the sooner we find something to drink, the better.” We left the tracks and hit the bricks.

Stopping at Frankie the Bum’s favorite bar, we sent Chuckie in for a dixie cup of water so we could gulp down our sedatives. Lewis and I hung outside on the boulevard trying to look small, nonchalant, and nondescript—which was of course impossible with my big, very-chalant and descriptive hair.

Lewis sensed my unease. “Y’know, cops wouldn’t expect people like us to be out in the open—”

“Yeah, it’s too fuckin’ stoo-pid!” I said. We laughed at ourselves. Cops were only part of our worries anyway.

“No, really! It’s too obvious!” he said, as if that were a point in our favor.

“Most people would have at least cab fare,” I said, lamenting our non-afterplan some more.

Chuckie emerged from the bar carrying a cup of water. “Cheers! Ha!” he said, handing it over to our outstretched hands.

There were two ways to get across Queens Boulevard. We ruled out the underground tunnel because of its limited escape routes. We could get trapped down there by cops, or worse. The other option was crossing all eight lanes above ground with the green lights. As we waited for the light to change in our favor, I was praying we wouldn’t have to run too fast—not after the way Lewis handled the roof. I didn’t even want to look up, because if you don’t look up it won’t find you. The light turned green and we committed ourselves to the crosswalk, unwilling to risk even jaywalking right now. With fake yawns to try and look bored and normal, we walked as if we were going home after a late shift at the post office.

I tried to calculate the sheer worth of our carryings, to keep my mind positive. The street value must have been in the thousands. To someone such as me, who lived on a sawbuck’s allowance plus the change I could garner through various methods, that was a whole helluva lot! It could buy a lot of freedom, even a trip to Europe and a search for my mythical Rue du Rogues.

As usual, the light turned against us before we were all the way across, but there were no cars coming so we kept going until we were ‘safely’ on the other side. Finally back on dark streets, a huge weight lifted off our shoulders, we relaxed a little and started daydreaming.

Lewis finally voiced what we were all thinking. “We did it man, we robbed a fuckin’ drugstore!” He said it as if we had just achieved enlightenment. I was feeling a little blissful.

“Like taking candy from a baby,” Chuckie added, grinning.

Lewis beamed. “This is the start of something big!” We knew, we knew..! Or at least we thought we knew. Certainly things were going to change in the near future. Multi congratulations were in order for a job well done. Bartender! Drinks for everyone!

“There’s a lotta cash ‘n hash in these bags,” I said. “What are you gonna do with yours?”

Lewis smiled, taking a moment to think about it. “First I’m gonna trade some of this for that black, African hash that’s going around, the real oily shit…” We all agreed. “Then I’m gonna get me the best meal I feel like, wherever I want.”

“Yeah!” we all agreed again. “Lobster at The Stratton! Yeah yeah! Every night!” Chattering along happily, we turned a corner and there, about forty feet in front of us, sat a parked cop car. Instant silence as we all saw it at once. Without breaking stride, because that would be too obvious, we discussed what we should do.

“What the fuck do we do now, boys?” I offered constructively.

“Cross the street?” Chuckie wondered.

“No!” Lewis quickly nixed that idea, adding: “Then it looks like we’re trying to avoid them. Keep walking. They wouldn’t expect us to just walk by like this.”

Small consolation, I thought, wondering what my bitch-name would be in jail. Then he added something which sent a chill up my spine: “I’ve got a plan.”

“Great, I’ve got Nembutals sticking up my nose and you’ve got a plan? What, run like hell at the last second?” Lewis stuffed the pill bottle deeper in my breast pocket and didn’t say anything as we committed to getting closer to our impending fate. My only consolation at this point was that the Tuinals we took should be coming on nicely soon, probably by the time we were safely tucked in our cells. In a few steps, we would know one way or the other how good Lewis’s plan was.

There was a light on inside the car. “Good, there’s only one of them,” Chuckie noticed first. “He’s probably doing his shift report, so he won’t give a shit about us. He wants to go home.” Chuckie was optimistic, but guessing. As the cop inside loomed larger than life, it’s what I told myself to believe. Sure, he won’t give a shit…

We tried to sound as if we were small-talking; still out of earshot, we mumbled garbles that we hoped sounded like normal, easygoing, natural conversation from a distance. Once we were right on top of him someone said (don’t ask me who): “Ummm-boy, can’t wait to get these steaks home after that double shift at the post office…”

Walking past, no more than three feet from our taxi to jail, I could see the cop scribbling on a clipboard. I don’t think he even noticed us until Lewis put his plan into action. Still clutching his bag, he practically stuck his whole head in the window, nearly tipping the contents into the cop’s lap, and said: “Scuse me sir, can you tell me the time?”

“?!” That was his fucking plan? I held my breath. With the break in stride, Chuckie and I almost collided into each other. My big hair felt like a circus tent with searchlights out front. The cop didn’t even glance up, but looked at his watch and said: “Two-fifteen,” without hardly a hitch in his scribbling on those important papers.

“Thank you!” Lewis added merrily, and walked away. We left the cop behind us, finishing his report about how he had kept the hamlet safe and sound that night from clowns like us.

I reminded myself to breathe. “That was your fuckin’ plan?” Chuckie thought it was brilliant. “What..? It was the stupidest fuckin’ thing you ever did, Lewis! And you’ve done some stoo-pid shit!”

Lewis defended himself. “It worked, didn’t it?”

“Did it? Only because he wanted to go home! Listen,” I told him seriously, “don’t you ever ask a cop what time it is after we’ve ripped off a drug store, okay?” Lewis laughed. “You’re fuckin’ crazy, man.” You couldn’t control Lewis. He was always going to do what he felt he should. I could only shake my head and keep walking.

Somehow we made it to the lobby of Jill’s apartment without further incident. Jesus, I thought, nearly exhausted physically but up-n-at-em mentally, I still have to eventually get home from here—some three miles away and across that fuckin’ boulevard again, alone. At least this stopover would provide a brief respite to the burden of success we had to endure, if she was home. Lewis pressed the buzzer. Painfully exposed like three pigeons on a fence, we waited.

“C’mon-c’mon-c’mon…” I muttered at the intercom.

“Come on, you lizard…” Chuckie’s greeting. We all snickered.

“Shhhh!” Without so much as a Who the hell is this? the door went BUZZZZZZZZZ and we scrambled for it, diving inside. I wish I had a photo of us as we rode up the elevator, the background music adding to the surrealism, waiting patiently for the eighth floor and grinning over our bags full of pills. Urban Gothic, I would have called it.

Jill gave us her best lascivious-slut look at the door. “Here a little late, aren’t you boys?” Wearing a loose robe and baggy night clothes, she looked like my idea of a gypsy fortune teller ready to mutter incantations over a large stromboli. Perhaps getting ready to read our fortunes on the carton of a frozen lasagna, she said: “Whatcha got there, food?”

We barged in, not answering. Once inside, there were hardy handshakes all around for a job done supremely well, beyond any of our expectations. We were ecstatic.

“Jill-baby,” Lewis said, “break out the brandy and three extra glasses. Oh, and a punch bowl, the biggest one you got!” He seemed to have an idea. “Let’s go in the living room.”

“Will a salad bowl be okay? I pawned the punchbowl…”

We hurried into the living room, where all celebration came abruptly to a halt. There, lying prone on the couch, was Miller, one of the neighborhood’s oldest, most thieving junkies. If he woke up and took a looksee at what we had going for us, pretty soon every thieving dope fiend around would be after our goods; and they wouldn’t pay or trade for it. This stash wouldn’t be worth a proverbial plugged nickel on the streets. It’d be up for grabs. Bargain day! At least while he was asleep there was still time for us to split, with him none the wiser.

On closer inspection, though, it was clear that he was more than just asleep, he was wasted. Spaghetti was falling out of his open mouth and slithering onto the couch. His girlfriend, a skinny blond with a bad complexion and dirty fingernails, sat nearby holding a bowl of the stringy stuff. Never fall asleep with spaghetti in your mouth, it looks bad.

“Yo,” we said, cautiously, unsure of whether or not to bolt.

As if answering our unspoken question, she told us he was hungry but too stoned to get up and eat. “He wakes up every once in a while and swallows, and I give him another forkfull,” she said. We looked at each other, then back at the spaghetti hanging out of Miller’s mouth, draped onto the couch. It was too funny not to laugh. We decided that staying was worth the risk, as he was probably too stoned to remember who we were even if he woke up from time to time to swallow. The bimbo we didn’t care about—she didn’t know us from Adam. “Whatcha got in the bags, anyway?”

We moved to the dining room, an empty space without table or chairs, like most of the apartment, and dumped the stuff all over the floor. A moment of awestruck silence prevailed. Then we began emptying our pockets, pants and sleeves and the small bottles in our socks and under our arms until there lay before us a three-foot mountain of drugs, glistening and sparkling like treasure in their pristine, lily-bright, lemon fresh, prescription filling, pharmaceutically bulk containers. The awe lingered like a spiritual moment, followed by breaking smiles, laughing, and finally even some square dancing and singing.

“We’re in the money, we’re in the money!” we sang, hooking arms and dancing around until we were all laughing on the floor and running the bottles through our hands as if they were gold doubloons. Suddenly we were four-year-olds again, emptying our bags of candy on Halloween. Jill broke out a fresh box of wine, the extra glasses, and brought in the salad bowl.

Lewis guided us. “Everyone drink a shot of wine!” We did, toasting our success. “Now pour all the Tuinals in the bowl.” Wheeeee! we said, my favorite! while opening up all the Tuinal bottles, large and small ones, and pouring them inside. “Now everyone take three glasses full and put them aside in your pile.” There were more left over. “Now another. Now another…”

That was how we divvied up the haul—well into the small hours of the morning. “Now Seconals!”

“Wheeee!” Now we were eight-year-olds, toasting our first shoplifting of the five-and- dime. Now Nembutals! Carbotral! On Valium, Miltowns, Phenobarbitals and Quaaludes! With Santa driving the sled, we loaded the little pills into our holiday sacks. Miller woke up from time to time and bellowed, “More spaghet…!” The blond stick-figure shoved more spaghetti in his mouth and we’d get quiet.

Whispering, followed by giggles. Now the ups! Dexadrine, front and center! Black beauties, take the stage! Cartwheels, Benzadrine, three glasses full! Then we started with the stuff we weren’t sure about. There were irregular shaped ones, speckled ones, tiny white ones… We’d sell these on the street as beat shit to people we either didn’t like or didn’t know, for cash flow.

“What is it?” they’d ask.

“What do you want?” we’d reply.

“Speed, man.”

“Here, take this. Twenty bucks.”

“How many do we take?”

They’d fork out the cash and come back for more. We wouldn’t know what the hell they’d be taking. Try two and lemme know how it works out, ok?

By the time we were done splitting it up, gray dawn was rearing its creepy head. Lewis took Jill into the bedroom and started banging her, thrashing the headboard against the wall as they did it. “Oh-oh-oh…” came the cadence while I tried vainly not to listen.

Miller had spaghetti going up his nose, a sight I didn’t want to face if he woke up. Between the downs and the wine, I was starting to get a serious nod going for myself and didn’t want to risk falling asleep on the dining room floor of Jill’s apartment—especially with Miller on the premises. I couldn’t afford to have him wake up and see me with my arms wrapped lovingly around my new stash. Now was the time to make the long journey home.

I kicked Chuckie, who was also starting to nod. “I’m splittin’, man. I want to get this shit home before my parents wake up.” He agreed that would be a good idea. “Hey Lewis,” I called through the door, “we’re splittin’, man.”

They were thumping away in there. “Oh-oh-kay…” came his staggered reply. “Hey!” he managed to add, “Not a word about this to anyone, oh-oh-kay? We-hee gotta let the hee-eat die down.” It was agreed, mu-ums the word.

Chuckie and I loaded up our stash and split. Out in front of the building, ready for the last leg of our trek, we could taste the ashtray flavor of another monochrome morning. “Good luck,” we said to each other, and headed down the street in opposite directions.

A few feet away, I remembered something and called after him, “Hey man, happy birthday!” Chuckie turned to look at me and seemed to remember that fact for the first time. Technically his birthday was the day before, but we weren’t through with that day yet. He smiled and laughed, great big guffaws all the way home.