Rated PG (situations)

Street of Rogues Ch. 1—Background Check

I don’t care what they say, I won’t stay in a world without love.—Peter and Gordon

When Winston Churchill resigned in 1955, life was black-and-white. Eisenhower was President. Polio was conquered. The AFL and CIO merged. Disneyland opened. The Bermuda Triangle was given a name. Ann Landers debuted, Bill Gates was born, and Oscar Mayer, who gave us baloney in a bag, died at 96. Lolita was published. CBS introduced The Johnny Carson Show. Captain Video was canceled but everyone loved Lucy and the Brooklyn Dodgers finally beat the Yankees in the World Series. As a reserved infant, I didn’t give a crap about any of this. I was sucking bottles—practicing for the cigarettes and coffee that came later.

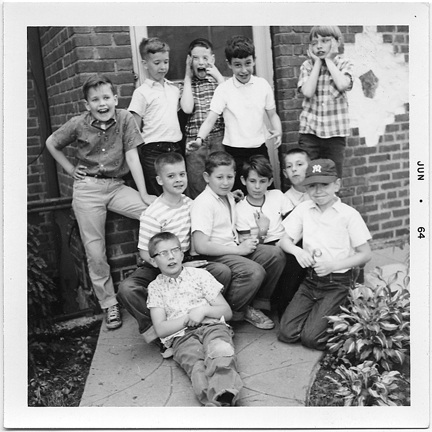

Technically, if baby-boomers are considered to have been born in 1946 through 1964, then June of 1955, when I was born, is the dead center of those years. In 1957, my father decided to take his Commercial Arts degree from Los Angeles to Madison Avenue. His high school sweetheart, my Ma, readily agreed—that’s how badly she wanted to put some distance between us and my grandparents. One set was too controlling, while the other was busy cultivating dysfunction through beer. Then age twenty-four, Pop had landed a job at a big ad agency. He found a walk-up in Brooklyn Heights, and Ma followed with me and my four-year-old sister. At the time, they thought it was a wonderful idea. The Brooklyn Dodgers thought the opposite and moved to LA.

After several moves, eventually we settled in Queens. We lived in an attached house with a faux-Tudor façade. Now predominantly Russian, Rego Park and Forest Hills were a mixed bag of Italian, German, Jewish, Irish, and WASP back then—with a sprinkling of Puerto Rican and ‘Negro’ thrown in for color. As far as my own heritage, all I knew was that Pop’s parents were Jewish, and Ma’s weren’t. Always in the throes of searching, we seemed to be none of the above. All my relatives were in California. I didn’t know what we were, and didn’t really care except on school holidays. As far as I was concerned, sitting in Church was an uncomfortable mixture of Boredom and Fear. If I wasn’t trying to stifle a yawn, I was thinking about this “burn in Hell for eternity” thing. I just wanted to ride my bike, have fun, and be among people who were always laughing.

I was smoking by the time I was twelve and already Spinning the Bottle to kiss girls—a fifth-grade Hugh Hefner, turtlenecks and all. The drugs came later, at thirteen, in junior high school. By New Year’s Eve in ’68, I was drunk on hard liquor and asleep in a roll-top desk.

Huffing glue came next, which was always full of surprises: such as coming back to consciousness in a fountain, or finding myself in the middle of an alley in the pouring rain listening to a far-off voice repeating: Why are you in the rain? Why are you in the rain? followed by laughter and the strains of some kid practicing his trombone from an apartment window nearby. The weirdness began in those already weird enough, hormone-induced adolescent years.

By junior high the hangout had changed. New school, new hangout, more kids. In the summer of ’69 you would find two hundred people at the park on any given night. What we fondly referred to as ‘The Park’ was actually the cement playground behind the school—a monolithic brick enclosure housing 2800 kids in three grades. There wasn’t a blade of grass near it. It contained the basketball courts, handball wall, and one giant baseball ‘field’ we used for bottle-rocket wars. Upwards of fifty guys stood out there, taking sides, before throwing bottle-rockets at each other. It tested your speed, to be sure, and pushed your luck. Little did I know the park would turn out to be my Shanghai Noodle Factory—a place where I would be nowhere, doing nothing. Russell Sage Junior High School, where no one knew who Russell Sage was and, more importantly, didn’t care.

We enjoyed the park at all hours, occasionally loosening the rope around the school flagpole for a spin into nausea. We also played ‘Johnny on the Pony’ there, with fifteen or more guys on a side—where getting knocked out was common, kicked in the balls expected, and legs were broken. This was a game where one team lined up by bending at the waist and holding onto the guy in front of him and so on, leading up to the ‘pillow’—the one guy at the head of the line standing with his back against a wall or a tree, acting as a cushion. The other team stood back some fifty paces and sent one guy at a time to run and jump on the backs of the ‘pony’ to try and break the line, in which case the jumping team got to jump again. By the time the last guy jumped it was hard to hold on, so you grabbed any dangling thing that might help keep you from hitting the ground first. If the line team (the pony) held strong for a count of three after all the jumpers were on, it was their turn to jump.

Payback was brutal and oftentimes gameplay ended abruptly; cops and ambulances showing up will do that, while concussions were simply moved to the side. High flyers like George the Cuban could sail the entire length of the pony and still manage to hang on. Of course, when he went too far the pillow usually got knocked out. That was bad, because there weren’t many volunteers to be the pillow. Usually only Fish did that, and he wasn’t really volunteering. When One-Ball Paul pronounced him the park ‘Mayor,’ he took on the task more willingly but still whined. The title of Mayor implied there’d be protection along with it—from everyone but George the high-flying Cuban.

Drugs were bought and sold at the park. Fights happened. Other gangs would occasionally show up; gangs of junkies, or worse, the Irish, looking for a rumble. The swifter kids left the premises while the slow ones took the brunt. The big guys, some of them adults, stood around to watch the carnage. The speedy kids waited around the corner until the coast was clear before ambling back in small groups to take up the revelry where it had so unceremoniously left off—not unlike a flock of gulls regrouping after a widespread scatter from dogs running down the beach. Those times were the most troubling while on acid, when getting beat up would quickly bummerize a trip. I was thirteen when I took my first hit of acid, with some seventy-five or so subsequent trips over the next few years.

Soon I was no longer buying Justice League comic books but hash, pot, booze, cigarettes and glue. To supplement my allowance, I rifled the old man’s pockets for loose bus fare and subway tokens—you could cash in tokens for two dimes to rub together. When that wasn’t enough, there was always panhandling. A career day for me was making four bucks in half an hour outside the busy 34th St. subway station. What a haul!

Then came the amphetamines.

Imagine a teenage boy, in great shape from playing handball for three to eight hours every day, riding a bike all over creation and often locking it up, getting on the train to Manhattan and walking another ten miles on any given night, imagine the energy he has when given a couple three-grain Dexedrines! In a group, chain smoking a pack each off just one match, we had to take turns talking because NONE OF US COULD SHUT UP WE JUST KEPT TALKING AND TALKING and little balls of spit would form in the corners of our mouth but you didn’t wipe it off because it just came back again anyway and BLAH BLAH BLAH all through the night without any commas until day broke and you could see the soot from the incinerators floating down to earth and you knew it was going to be oppressively hot and another day which began with the question WHAT DO WE GET HIGH ON NEXT? Depression, the cotton mouth of an ashtray, the burrs in the eyes, they all came with the humidity of another summer’s morn.

Then came the barbiturates.

A drunk without the barf, how cool is that? In those days, pharmaceutical Seconal and Tuinal sold for three for a buck (an ‘ace’) on the street. You only needed two, otherwise you were worthless, so it made better sense to buy six for a deuce and split it three ways. Cheap high, and nothing hurt, ever. I fell asleep once holding a lit smoke and woke up with the filter butt, hollow and cold, between my fingers—and a raw burn-hole just above my fingernail.

On the heels of barbiturates came heroin and Blue Morphan, winter drugs. With a five dollar tab of pharmaceutical Blue Morphan (essentially morphine) you could weather a blizzard in a tank top. Mainlining was the only efficient way to truly take advantage of either. Over those five years, thirteen through seventeen, it got so that anything was worth trying to get high. At parties we scanned the parents’ medicine cabinet in the bathroom for anything ending in -al or -drine. Stuff we weren’t familiar with was taken first and asked questions about later—in one case ending up with blood pressure pills and ‘snappers,’ amylnitrate, which was used for jumpstarting someone’s heart if necessary. If I snorted one now I’m pretty sure my heart would explode, but at fifteen it was a nice, if short, rush. Romilar cough syrup, Carbona cleaning fluid, even separating the codeine granules out of a Contac capsule wasn’t too far beneath us. We were idle hands in the Devil’s pharmacy.

At fifteen I already had a moustache and long hair. Well, big hair would be more accurate. It didn’t grow long, it grew wide. Approaching six-feet tall, I weighed 110 pounds—in wet clothes. I was gaunt and haunted looking, maybe even a little scary. I looked old enough to be served in many bars in the city, which was eighteen at the time. My life revolved around scheming for drugs and keeping away from the Bad Guys in the neighborhood. And getting laid, of course.

My closest friends were all older than I was by at least a year, left back in school until we were all finally in the same grade, in the dumbest classes. My ninth-grade class consisted of druggies, rumblers, the dyslexic, the narcoleptic and epileptic, and the school basketball team. Classes were numbered from the smartest to the ‘most likely to fail.’ Our class, the last one, was 9-11—a numeric connection to future calamity. Teachers were afraid of us. Administrators left us alone in our cage with them—their backs against the wall and sometimes even shoved into a closet for the period.

Nothing was sacrosanct. We stole freely from each other. If someone pissed you off, even a little, it was okay to steal his TV or parents’ camera and pawn it downtown. Even if they didn’t piss you off, what they wouldn’t know couldn’t hurt us. Eventually the only Golden Rule was: Never give names to the cops. It was the pirates’ code; defy that and you’re fucked.

Friends, jonesing for smack, were stabbing friends over sour drug deals and leaving them to die in the bushes. Tough guys were murdered by tougher guys, or by cops. Jew, German, Irish, Black, Cuban—it didn’t matter, the Unbreakable broke. In those five years, the thieving got worse, the winters colder every year, and young teenagers were scattered in bars across the city like seasoned barflies with their heads down, nursing beers to keep from the cold, and scheming, always scheming.

By 1970, the era of “love the one you’re with,” the draft was in full force. Our once-proud cast of hundreds who gathered in the coliseum we called our park was losing the battle of attrition to jobs, Nam, murder, jail, and fleeing to Florida or California to escape prosecution for such crimes as possession and sale of drugs, breaking-and-entering, armed robbery and sometimes worse. Some fled to Canada after getting draft notices. Some went off to college, mostly party schools like New Paltz in upstate New York, where the beer was cheap and the girls plentiful—or maybe it was the other way around. I don’t know because I never went to college.

It was only a matter of time before my luck ran out, I knew that for a fact. It helped to have a dream.

mitchell I know I knew you during some of this time like hanging out at the park sounds so familiar How do we order your book.

Hiya Debi. This book is unpublished. It needs an agent or publisher (if you know any). It’s actually two books… sort of a “Fall and Rise of…” I get the feeling that the neighborhood is much different now that it’s not overrun by teenage babyboomers. Thanks for being interested! Mitch.